Using JSON as a configuration format is (usually) a mistake.

Not a preference. Not a style choice. A normalized architectural mistake, and a very normalized one.

People get uncomfortable with that sentence because JSON works. And in tech, once something works, we collectively agree to stop asking if it actually makes sense, and we start building religions around it.

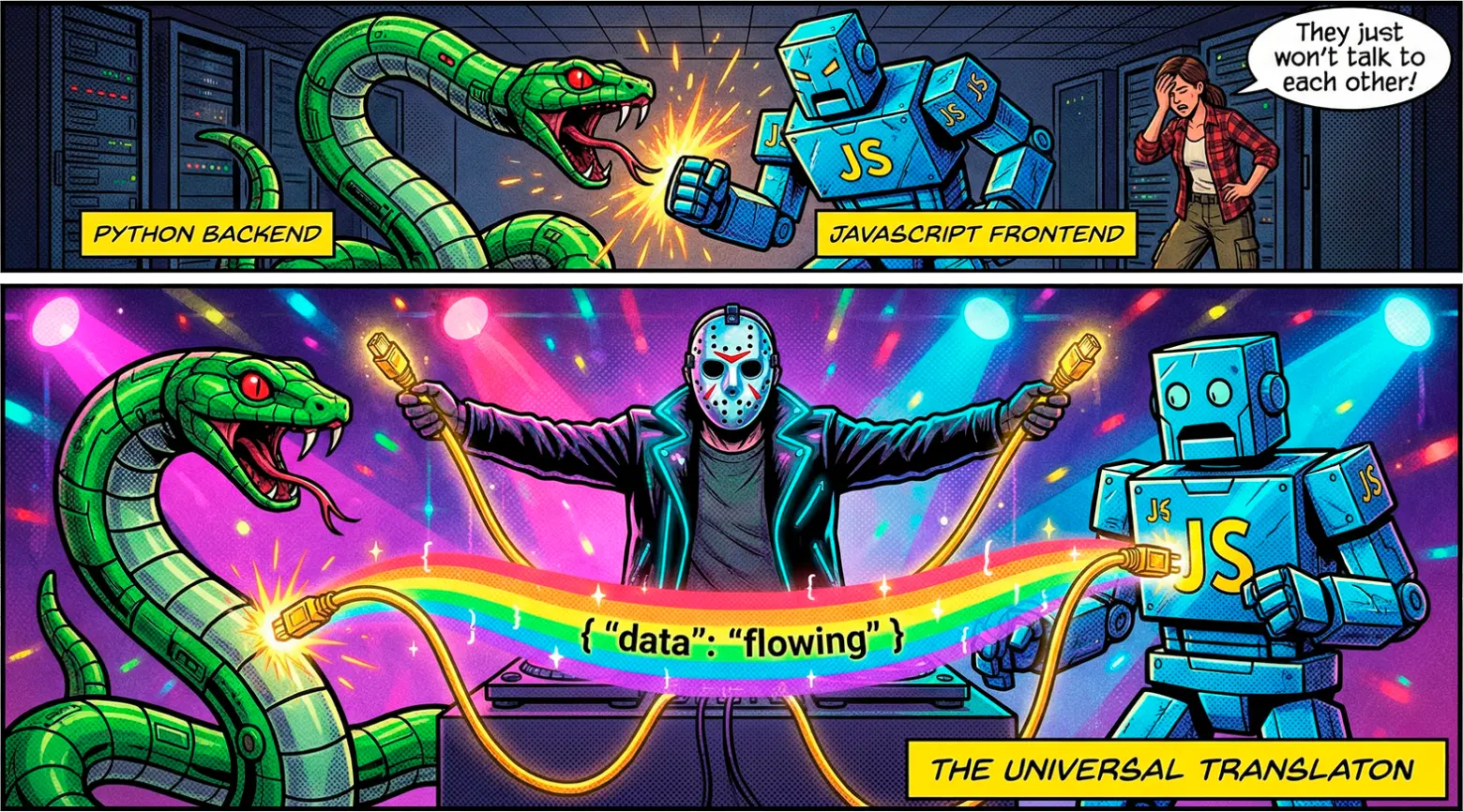

Let’s be clear, JSON is a massive success. As a transport format, it’s basically unbeatable: predictable, deterministic, boring in the best way, trivial to parse, trivial to generate, everywhere. Machine-to-machine, JSON is fantastic. The problem starts when we look at a format designed to be produced by computers, and decide it should also be written, read, reviewed, versioned, and maintained by humans, as if we were also computers, just slower.

We are not.

And yes, “but my editor formats it” is not an argument. That’s like saying a chair made of nails is fine because you bought good pants.

This is not an attack on JSON. This is an attack on the industry habit of using the right tool in the wrong place, then acting surprised when the people writing it start to hate their lives.

Why JSON won

JSON didn’t win because it’s expressive. It won because it’s limited, consistent, and boring. That’s an enormous advantage when two systems that don’t know each other need to exchange data without negotiating intent, context, and interpretation.

It’s a small closed format. No clever shortcuts. No “oh but in this case”. No magical semantics. Just primitives and structure. That is exactly what you want for contracts. When someone says “my API speaks JSON”, everyone understands the shape of the deal instantly. No surprises. No creative interpretations. No YAML-level philosophical debates about what on means.

As a transport format, JSON deserves all the respect it gets. If the file is machine-generated, rarely touched, and validated by a strict schema, JSON on disk is fine. My problem is human-authored JSON pretending to be a friendly authoring format.

Where everything starts to go wrong

The moment you decide humans should author JSON, you are effectively saying: “the syntax matters more than the intent”. You don’t say it out loud, but that’s the outcome.

This usually doesn’t come from malice. It comes from laziness dressed up as simplicity: “the system consumes JSON, so people should write JSON”. It sounds logical. It’s also the kind of logic that produces self-inflicted pain at scale.

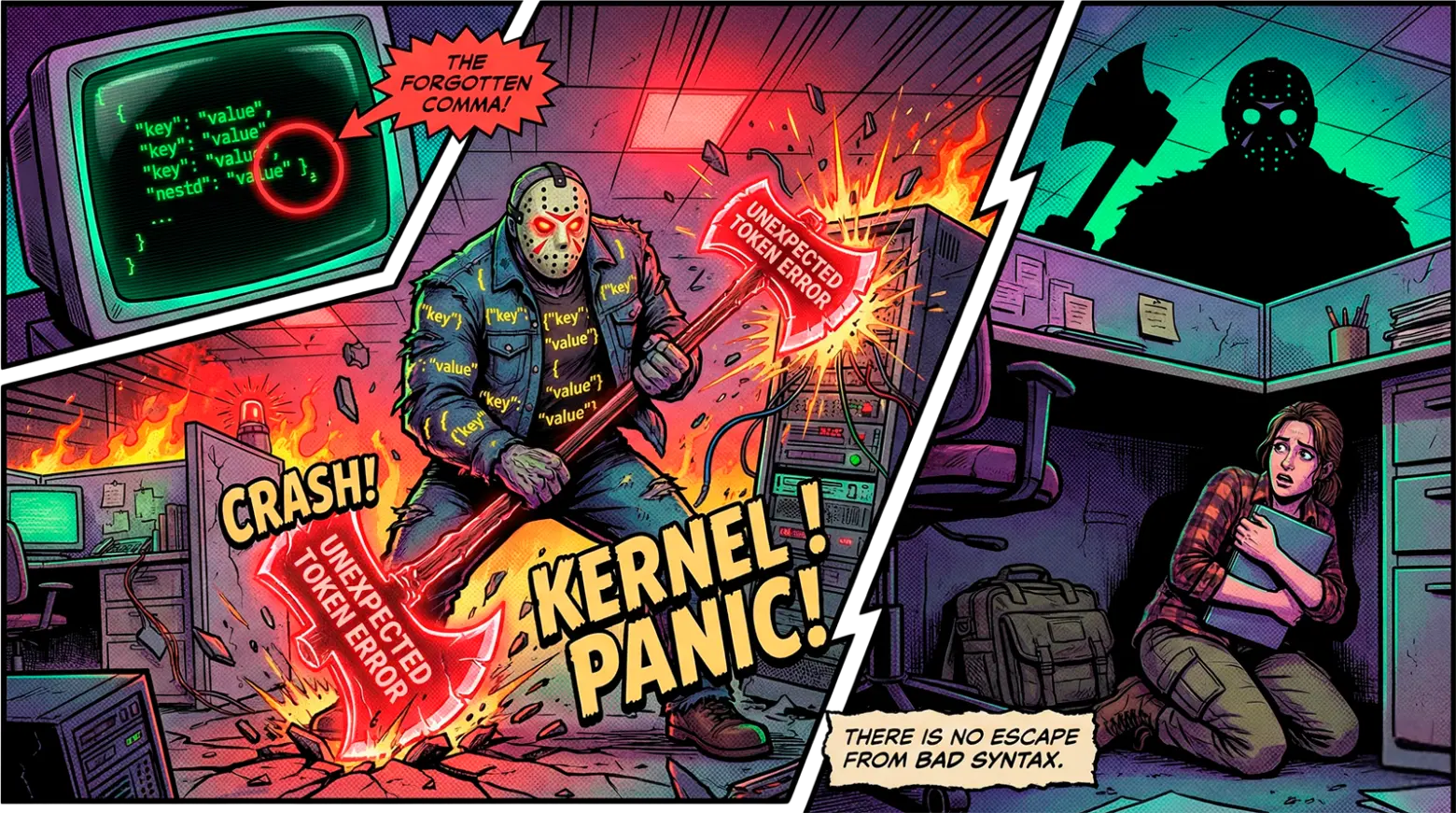

JSON demands perfect syntactic precision to express even the smallest idea. One missing quote, one comma, one bracket, and everything breaks. There is no “kind of broken”. There is only “parse error” and the conversation is over.

For machines, that’s fine. For humans, that’s hostile.

And before someone says “skill issue”, go edit a large IAM policy JSON at 2am, push it, break production, and then come back to lecture everyone about how “it’s simple, actually”.

JSON is structurally hostile to humans

This isn’t taste. It’s structural.

JSON has no comments. JSON is verbose. JSON makes you repeat yourself. JSON makes you care about commas and quotes more than meaning. JSON has no way to express intent, only structure. So people start inventing conventions and superstitions:

- “this key is optional, but only in this scenario”

- “this value is a string, but it behaves like an enum, except when it doesn’t”

- “this section is deprecated, but still required because reasons”

- “don’t touch this block unless you like pain”

And because JSON can’t carry context, the context leaks elsewhere: README files, Confluence pages, Slack messages, tribal knowledge, “ask João”. Your configuration stops being configuration and becomes a scavenger hunt.

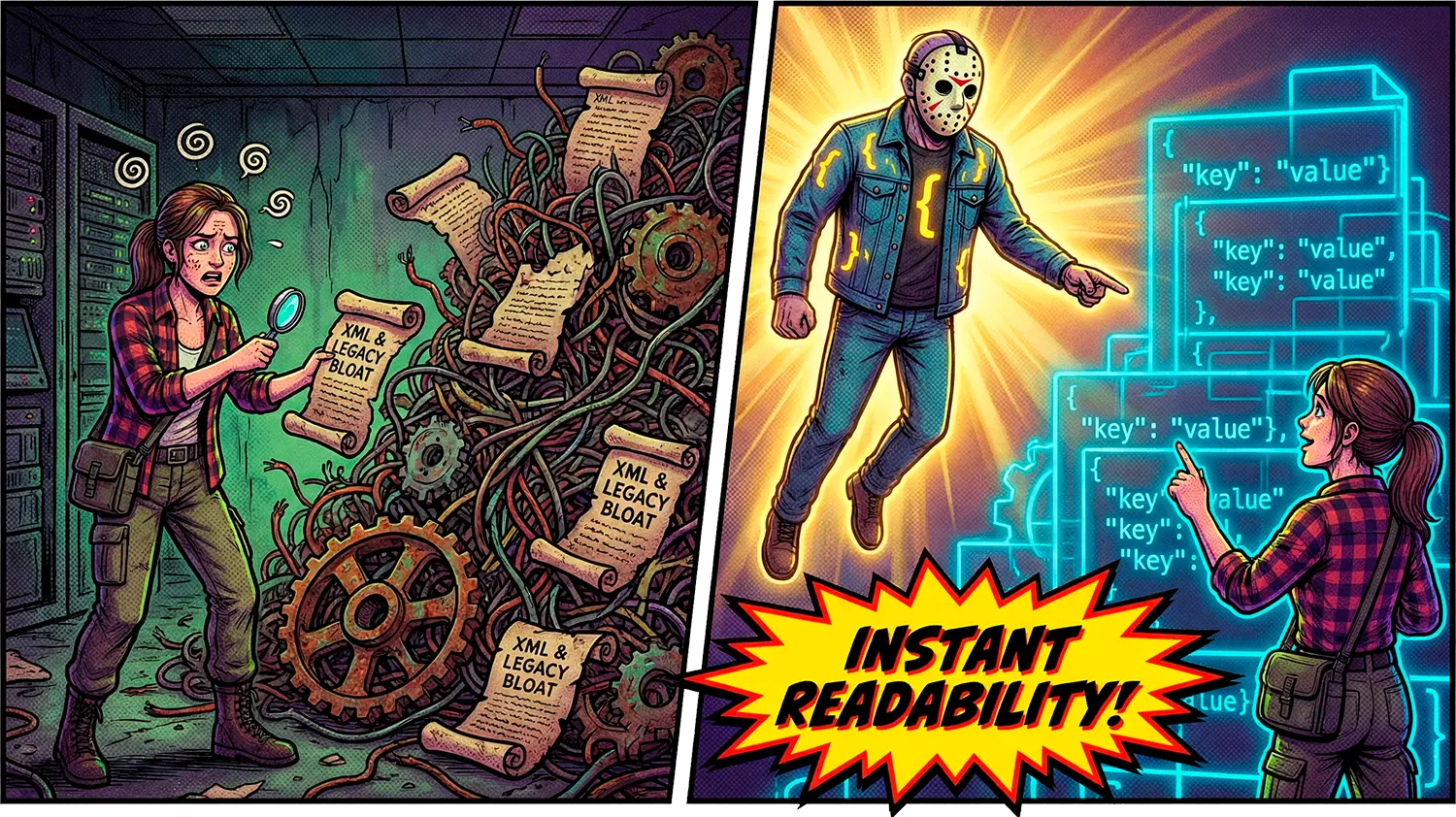

When you see a big hand-written JSON file, it rarely communicates clarity. It communicates resistance. It communicates that someone suffered, and the only reason it still exists is because everyone agreed to pretend this is normal.

JSON configuration is a normalized mistake

Configuration, by definition, is something humans will read, write, review, version, and argue about in pull requests. It carries intent. It needs context. It benefits from comments. JSON provides none of that, by design.

So what happens? We create these beautiful 300-line objects full of tiny flags, where one comma can invalidate the entire thing, and then we ship the “documentation” somewhere else. Review becomes painful. Change becomes scary. And the final experience is basically “it works, but it works powered by spite”.

Examples everyone knows:

tsconfig.json: it’s not the worst offender, but it’s the perfect illustration of “human-authored JSON that wants comments really badly”.package.json: scripts, tool configs, overrides, it becomes a dumping ground because it’s convenient, not because it’s good.- Any complex policy config (permissions, rules, routing, workflows): JSON turns your domain into punctuation management.

And yes, you can add tooling. You can add schemas. You can add validators. You can add prettier. You can add a UI that generates JSON. Notice something? The more serious your system gets, the more you move humans away from writing JSON. That’s not a coincidence. That’s your own architecture admitting the truth.

The pro-JSON argument

“But JSON is simple. Everyone knows it.”

Everyone knows a lot of things that are terrible tools for certain jobs.

Everyone knows regular expressions too. That does not mean we should store business logic as regex strings inside a JSON file and call it “configuration”. Familiarity is not a tool-selection criterion. Fitness for the problem is.

JSON is simple to consume, not simple to author. And that distinction matters a lot more than people want to admit.

Authoring formats exist for a reason

If the config is meant to be written by humans, use a format designed for humans.

TOML exists for a reason. HCL exists for a reason. Even YAML exists for a reason, and yes, YAML has its own problems, and anyone pretending YAML is “clean” has probably never debugged a weird parsing edge case on a Friday night.

But the point stands: authoring formats usually allow comments, are more readable, and reduce the cognitive cost of writing. They let people think about the domain first, and the representation second.

Also, a lot of “good” systems already follow this pattern:

Humans write something expressive. Machines validate and normalize it. JSON only shows up at the boundaries, when data needs to travel, or when it becomes a strict contract between systems.

That separation is not bureaucracy. It’s respect for human limits.

The pipeline that avoids unnecessary suffering

In well-designed systems, the flow is usually:

- Humans author something expressive, comfortable, and reviewable.

- The machine validates it, transforms it, normalizes it.

- JSON appears only when it must: transport, persistence, interop.

If you want typed configuration, TypeScript can be amazing, because types and tooling actually work in your favor. If you want “configuration people can read and discuss”, TOML/YAML/HCL or a small DSL is often a better fit. If you want system-to-system contracts, JSON is still the king.

The pattern repeats in modern tools because it works. It respects human limitations and exploits machine strengths. Forcing JSON from the start skips the sane pipeline and pushes all the cost onto the people who should pay it the least.

Hater or fan?

I still love JSON where it makes sense: contracts, APIs, serialization, machine-to-machine communication.

I still hate JSON when someone expects me to write, review, and maintain complex rules in it, as if that were a normal human experience.

This is not elitism. It’s not a trend. It’s not stubbornness.

It is basic respect for the people who have to deal with the code.

JSON does not need to be omnipresent to remain valuable. It just needs to stay in the right place.

And that place is definitely not between you and the keyboard at two in the morning.